Lowry At Home, Salford 1966

Visitors passing through the doors of The Lowry's latest exhibition are immediately greeted by a striking image of the man himself, fixing them with a somewhat bemused glare from behind the net curtains of his house in Mottram in Longdendale.

The photo is the first of those taken by Clive Arrowsmith, working on a commission from Nova magazine. Arrowsmith caught his subject off-guard with his initial shot: LS Lowry appears surprised (and perhaps a little wary) to have guests at The Elms, his final home. Nonetheless, across two days in the mid-1960s Arrowsmith was granted unparalleled access to Lowry's private world. His remarkable collection of photographs forms the basis for Lowry At Home, Salford 1966.

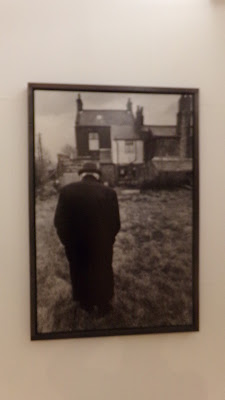

The large, black-and-white photographs which adorn the spacious exhibition space tell an unseen, domestic story of LS Lowry. Arrowsmith takes us to Lowry's workroom (a jumble of empty frames and brushes) and his simple kitchen (complete with an empty milk bottle standing on the windowsill and laundry drying over the stove). Outside, Lowry poses in a gloriously unkempt garden - which he later admitted went untouched for three years before Arrowsmith arrived at his door.

Lowry At Home is as much a reflection of the city of Salford in 1966 as it is of the artist himself. Arrowsmith's photos provide a powerful social commentary on a decade which is so often wrongly portrayed as the "swinging sixties." There are few indications of a triumphant world cup campaign or upcoming "summer of love" in the smog-ridden shots of Salford. Instead we see a gloomy industrial landscape dotted with closed-down shops and solitary mothers maneuvering prams along deserted terraces.

In the age of the exciting, rebellious music of The Who and The Rolling Stones, or the sexually-charged mania induced by The Beatles, Arrowsmith's photographs of Lowry's world are more comparable to the nostalgic songwriting of The Kinks' Ray Davies. Images of grey Salford skies and the Lowry's humble home resonate strongly with songs such as Dead End Street (1966) and Autumn Almanac (1967). The former narrates a life of urban poverty and bemoans a lack of financial prospects:

There's a crack above the ceiling

And the kitchen sink is leaking

Out of work and got no money

Sunday joint of bread and honey.

The later, more upbeat, details the simple pleasures of working class life: football on a Saturday, roast beef on Sunday and a yearly holiday to Blackpool. There is a joy to the lyrics, but also an air of sadness. The singer is resigned to his repetitive urban life. "This is my street and I'm never gonna leave it," he declares, "and I can't get away..."

Arrowsmith conveys in this photography what Davies conveys in his music: the reality of everyday life in the 1960s. It was not always new and exciting, not always glamorous and forward-thinking. More often than not it was mundane and gritty, encapsulated in the chips in Lowry's tiles and the missing cobbles on Salford's streets.

That is not to say that the considerable social changes of the decade passed Salford and Lowry by completely. Slum clearance and urban regeneration were slowly but surely changing the face of the landscape seen in Lowry's most renowned work. Northern working-class voices were getting the chance to air their grievances in plays and dramas such as This Sporting Life (1963). Nova magazine was itself an exceptionally progressive, albeit short-lived, publication which covered previously-taboo themes such as contraception and homosexuality.

|

Arrowsmith's photography, however, grounds us once more. There are no glamorous models to be found here, merely a less than enthusiastic thirteen-year-old keen to finish shooting before her chips grow cold.

It would appear that, though Lowry played only a minor role in this particular social revolution, he is perfectly happy within his world. It is often commented that Lowry would rarely smile, instead composing himself sternly and seriously. Yet a certain warmth is reflected throughout Arrowsmith's photos. With the exception of his surprised expression in Arrowsmith's first photo, he appears relaxed, often displaying something of a carefree indifference towards the camera. In the shots taken in his bedraggled back garden, Lowry is positively grinning.

This enchanting exhibition prompts us to reevaluate LS Lowry's experience of the so-called "swinging sixties." The way in which his environment is presented as so basic and mundane is at first a little perturbing, but the glint of satisfaction in the eye of the old artist is reassuring. Just as his paintings had done to the factory workers of Salford decades before, Arrowsmith's photos normalise Lowry. For the briefest of moments he is not the celebrity artist. He is just an individual making his way around his city.

And with that, he is content.

Lowry At Home, Salford 1966 is open now at The Lowry, Salford Quays - world class arts centre and proud home of Quaytickets. Click here to find out more about the excellent range of events and performances.

Comments

Post a Comment